Paper by Sean Powell - Gold Coast Based Wills and Estates Solicitor at Robbins Watson Solicitors

FORWARD

I recently presented to other solicitors at a Wills and Estates Seminar for LegalWise on the topic of “Estrangement in Family Provision Applications”. This paper was prepared in support of that presentation. Although the intended audience is wills and estates practitioners, people who are considering bringing a family provision application (contesting a will or estate) in circumstances where they are estranged from the deceased person may find the article informative. It should also be of assistance to executors and administrators who are tasked with defending a family provision application when one or more of the applicants were estranged from the deceased.

INTRODUCTION

Due to advances in modern medicine and a range of other factors, we can now expect to live significantly longer than our recent ancestors. While this is generally good news, our increased life expectancy has brought with it a greater risk of disease, disability, dementia and advanced ageing prior to death.1 These issues occur in what are increasingly complex social circumstances and family organisation (i.e. the blended family), at a time when testators are dying with more valuable estates than ever before. As a result, family disagreement and breakdown are more likely to occur, when the viability of estate challenges is increasing. It is of course no surprise, that the occurrence of family provision applications is rising.

There is nothing to suggest this trend will not continue, particularly as the baby boomer generation ages, which will lead to the largest transfer of wealth in human history.2

Unsurprisingly, estrangement is one of the most common factors cited by a testator when making the decision to disinherit a potential object of their bounty, usually an adult child. To properly advise a testator when their will instructions are taken, it is critical that estate planners have a sound understanding of the law relating to how an estrangement is dealt with in an application for further provision. The same applies to litigators, when advising executors and applicants on the prospects of an application for provision when the applicant was estranged from the deceased.

This paper discusses the features of estrangement, the interplay between estrangement and the testator’s moral obligation, and various case examples involving estrangement in different circumstances. It also provides practical guidance on how to take fulsome instructions and appropriately advise clients from the outset.

WHAT IS AN ESTRANGEMENT

The Macquarie Dictionary defines “estrangement” as: “to turn away in feeling or affection, to alienate the affection of, to remove or keep at a distance”.

It is derived from the Latin root “extraneus” which means “foreign, from without” and from Vulgar Latin “extraneare “to treat as a stranger”.

HOW IS ESTRANGEMENT DEALT WITH IN FAMILY PROVISION APPLICATIONS?

Legal principles

Section 41(1) of the Succession Act 1981 (Qld) provides:

“41 Estate of deceased person liable for maintenance

(1) If any person (the deceased person) dies whether testate or intestate and in terms of the will or as a result of the intestacy adequate provision is not made from the estate for the proper maintenance and support of the deceased person’s spouse, child or dependant, the court may, in its discretion, on application by or on behalf of the said spouse, child or dependant, order that such provision as the court thinks fit shall be made out of the estate of the deceased person for such spouse, child or dependant.

In Queensland, the statute does not prescribe any particular factors to be taken into account when determining what is “adequate” or “proper”.

The relevant factors were identified in Singer v Berghouse3, where Mason CJ, Deane and McHugh JJ identified two questions or stages in resolving family provision applications:

“The first question is, was the provision (if any) made for the applicant ‘inadequate for [his or her] proper maintenance, education and advancement in life’? The difference between ‘adequate’ and ‘proper’ and the interrelationship which exists between ‘adequate provision’ and ‘proper maintenance’ etc. were explained in Bosch v. Perpetual Trustee Co. Ltd. The determination of the first stage in the two-stage process calls for an assessment of whether the provision (if any) made was inadequate for what, in all the circumstances, was the proper level of maintenance etc. appropriate for the applicant having regard, amongst other things, to the applicant’s financial position, the size and nature of the deceased’s estate, the totality of the relationship between the applicant and the deceased, and the relationship between the deceased and other persons who have legitimate claims upon his or her bounty.

The determination of the second stage, should it arise, involves similar considerations. Indeed, in the first stage of the process, the court may need to arrive at an assessment of what is the proper level of maintenance and what is adequate provision, in which event, if it becomes necessary to embark upon the second stage of the process, that assessment will largely determine the order which should be made in favour of the applicant. In saying that, we are mindful that there may be some circumstances in which a court could refuse to make an order notwithstanding that the applicant is found to have been left without adequate provision for proper maintenance. Take, for example, a case like Ellis v. Leeder, where there were no assets from which an order could reasonably be made and making an order could disturb the testator’s arrangements to pay creditors.”

The reference to Bosch v Perpetual Trustee Co Ltd4 in the above judgment notes the emergence of the concept of a “wise and just testator”, which served to moderate a testator’s reasons for denying an inheritance to an eligible person in circumstances where they are irrational or extreme. The court will consider what a ‘wise and just testator’ would have done, but not “a fond and foolish, husband or father.”5

The first stage of the test necessarily involves an evaluative balancing of the relevant considerations (from the perspective of a wise and just testator), being the applicant’s financial circumstances, the size of the estate, the totality of the relationship between the applicant and the deceased, and the relationship between the deceased and others with legitimate claims.6

It follows that estrangement will be considered as a part of the totality of the relationship between the applicant and the deceased, balanced against the other relevant considerations.

Relevantly, in Lathwell v Lathwell7, the Court said:

“The word ‘estrangement’ does not in fact describe the conduct of either party. It is merely the condition which results from the attitudes or conduct of one or other or both of the parties. If the estrangement is entirely caused by the unreasonable conduct or attitudes of the testator and sustained by the unreasonable conduct of the testator, then the estrangement alone could not amount to disentitling conduct on the part of the applicant.”

In other words, an estrangement is but one factor to be considered in the overall exercise of the court’s discretion to determine whether or not further provision should be made for an applicant.

With respect to the Court’s discretion, in White v Barron8, Stephen J said:

“[T]his jurisdiction is pre-eminently one in which the trial judge's exercise of discretion should not be unduly confined by judge-made rules of purportedly general application.”

In Kay v Archbold [2008] NSWSC 254 at [126], White J described the assessment of proper provision as

“… an intuitive assessment. …”

The takeaway being that it is very difficult to provide an accurate assessment of the impact an estrangement will have on the quantum of an order for further provision prior to the hearing.

Adult children

In most cases (but not always) involving estrangement, the estranged applicant will be an adult child, which necessitates some consideration of how the court considers applications by adult children.

In Re Sinnott9, Fullagar J said:

“No special principle is to be applied in the case of an adult son. But the approach of the court must be different. In the case of a widow or an infant child, the court is dealing with one who is prima facie dependent on the testator and prima facie has a claim to be maintained and supported. But an adult son is, I think, prima facie able to ‘maintain and support’ himself, and some special need or some special claim must, generally speaking, be shown to justify intervention by the court under the Act.”

In Hughes v National Trustees Executors and Agency Co of Australasia Ltd10, Gibbs J said:

“In some cases a special claim may be found to exist because the applicant has contributed to building up the testator’s estate or has helped him in other ways. In other cases a son who has done nothing for his parents may have a special need. This may be because he suffers from some physical or mental infirmity, but it is not necessary for an adult son to show that his earning powers have been impaired by some disability before he can establish a special need for maintenance or support. He may have suffered a financial disaster; he may be unable to obtain employment; he may have a number of dependents who rely on him for support which he cannot adequately provide from his own resources. There are no rigid rules; the question whether adequate provision has been made for the proper maintenance and support of the adult son must depend on all the circumstances – that is, on all the facts that existed at the date of the death of the testator, whether the testator knew of them or not, and all the eventualities that might at that date reasonably have been foreseen by a testator who knew the facts.”

In Wheat v Wisbey11, Hallen J outlined the relevant considerations with respect to adult children:

- “The relationship between parent and child changes when the child leaves home. However, a child does not cease to be a natural recipient of parental ties, affection or support, as the bonds of childhood are relaxed.

- It is impossible to describe in terms of universal application, the moral obligation, or community expectation, of a parent in respect of an adult child. It can be said that, ordinarily, the community expects parents to raise, and educate, their children to the very best of their ability while they remain children; probably to assist them with a tertiary education, where that is feasible; where funds allow, to provide them with a start in life, such as a deposit on a home, although it might well take a different form. The community does not expect a parent, in ordinary circumstances, to provide an unencumbered house, or to set his or her children up in a position where they can acquire a house unencumbered, although in a particular case, where assets permit and the relationship between the parties is such as to justify it, there might be such an obligation.

- Generally, also, the community does not expect a parent to look after his, or her, child for the rest of the child’s life and into retirement, especially when there is someone else, such as a spouse, who has a primary obligation to do so. Plainly, if an adult child remains a dependent of a parent, the community usually expects the parent to make provision to fulfil that ongoing dependency after death. But where a child, even an adult child, falls on hard times, and where there are assets available, then the community may expect a parent to provide a buffer against contingencies; and where a child has been unable to accumulate superannuation or make other provision for their retirement, something to assist in retirement where otherwise, they may be left destitute.

- If the applicant has an obligation to support others, such as parent’s obligation to support a dependent child, that will be a relevant factor in determining what is an appropriate provision for the maintenance of the applicant. But the Act does not permit orders to be made to provide for the support of third persons that the applicant, however reasonably, wishes to support, where there is no obligation of the deceased to support such persons.

- There is no need for an applicant adult child to show some special need or some special claim.

- The adult child’s lack of reserves to meet demands, particularly of ill health, which become more likely with advancing years, is a relevant consideration. Likewise, the need for financial security and a fund to protect against the ordinary vicissitudes of life, or has a limited means of earning, an income, this could give rise to an increased call on the estate of the deceased.

- The applicant has the onus of satisfying the court, on the balance of probabilities, of the jurisdiction for the claim.”

Application of the legal principles to estrangement – will the moral duty override estrangement?

What do the cases say?

In Palmer v Dolman12, Ipp JA said:

[T]he mere fact of estrangement between parent and child should not ordinarily result, on its own, in the child not being able to satisfy the jurisdictional requirement under the Act.

In Wheatley v Wheatley13, Bryson J said in the leading judgment:

I do not regard a state of estrangement or even hostility as necessarily bringing an end to any moral duty to make provision for an eligible person, whether wife, son, daughter or other. When there is an estrangement the application of s 7 requires that it should be appraised and its causes should be considered. A long-standing severance of a relationship with a parent, or even a clearly-established termination of all communication is not in the present to be regarded as necessarily putting an end to moral duty; it may do so, but whether it does calls for an appraisal in each case and is not reduced to clear principle. Respectful submission to paternal wishes, even if they are reasonable, is not a condition of paternal duty. A whole view of the relationship and the character and conduct of both parent and child should now be taken, and the influence of character can be complex. Sometimes people’s characters cause them to be poorly disposed towards their parents, and the influence of this on a parent’s moral duty is not solely adverse to the child: people’s behaviour is influenced by their characters in ways from which few can escape, and of all people their parents must have had the most time and opportunity to influence character, understand it, become reconciled to it and tolerate its workings when unpleasant.

In another age a different interpretation of the community’s sense of moral duty was probably correct, but it is my task to interpret moral duty in my own times. The idealised just and wise testator of the present age knows now that he should not expect submission to his wishes, and knows that his children will be themselves no matter whether he likes it or not, and that they will feel free to interact with any hostile or unreasonable conduct of his own. Courts no longer attribute the characteristic of being stern to the idealised testator, reflecting a marked change in perceptions of moral duty since 1910 when Edwards J spoke in Allardice v Allardice (1910) 29 NZLR 959 at 973 of a father who was just and stern but no loving. Long periods of hostility or estrangement are not inconsistent with successful applications and the contribution of the testator is examined: see for examples Gorton v Parks (1989) 17 NSWLR 1, Howarth v Reed , Powell J unreported 15 April 1991.

In the case of Foley v Ellis14, the Court found both the applicant (an estranged adult daughter) and her mother had both behaved in a manner that was hurtful to one another. Under her will, the testatrix left $1.1 million each to the applicant’s siblings and only $165,000 to the applicant, plus $165,000 to each of the applicant’s two children. Sackville AJA said:15

The more recent authorities have held that a state of estrangement or even hostility between a testator or testatrix and a claimant does not terminate the obligation of the testator or the testatrix to provide for the claimant.

Events viewed years later through the cold prism of a courtroom may give a different impression than when the events are set in the context of the raw emotions experienced at the time. The ‘wise and just’ testator or testatrix … must be taken to understand this.

The implication being that conduct regarded by the testator and litigants as very serious may be regarded by the Courts as not so serious or even trivial.16

The applicant’s provision was increased to $500,000, which fell rateably on her two siblings, with her children’s shares undisturbed.

In the Tasmanian case of Doddridge v Badenach17, the deceased left his entire estate (about $600,000) to his stepson. The plaintiff was his only biological child and they had been estranged for many years. At [47], Evans J said:

I have no hesitation in concluding that the applicant, being the testator's daughter, coupled with the other matters that have been referred to, in particular his failure to fulfil his obligations to her during her childhood, he was subject to an obligation to provide for her out of his estate. She was his only child. That he had substantially repudiated his obligations to her during her childhood, did not absolve him of the obligation to provide for her upon his death and, if anything, it reinforced that obligation. Although his best opportunity to support her was past by the end of his life, she remained in need of his support, and insofar as he was able to do so, he was obliged to provide it.

The daughter received an award of $200,000 in further provision, plus costs.

In Wright v Wright18, the testator gifted his estate to the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation (Queensland) and his three siblings, while leaving no provision for his adult children who he had been estranged from since 1979 (34 years). The estate had a gross value of approximately $1,875,000, subject to legal costs.

Both applicants had financial need, particularly in comparison to the competing siblings. However, the siblings maintained close and loving relationships with the deceased, while the children did not.

However, Devereaux SC DCJ commented at [31], that the applicants’ relationship with the deceased was “largely characterised by his absence”. He also observed that both the applicants and the deceased felt abandoned by the other. The court noted a number of unsuccessful attempts were made by the applicants to reconcile with their father, but he did not reciprocate.

After considering the reasons for the estrangement, the Court found the main reason for the long estrangement was the deceased’s conduct towards his children.

The Court held that the estrangement did not disentitle the applicants from provision but cited Wheatley v Wheatley19, where Bryson JA said that the poor relationship between the applicants and the deceased “operates to restrain amplitude in the provision to be ordered.”

The applicants received further provision of $350,000 and $400,000, respectively.

Christie v Christie20 is an example of a case where the claim of an estranged adult son’s application was dismissed where he was found to have been physically violent to his mother. The estate was valued at approximately $900,000 and the applicant was her only surviving child, with his four siblings predeceasing the deceased.

The son claimed to be a “lame duck”, in that he was in a poor financial position with limited prospects of improving his situation. He also claimed to be a dutiful and loving son, and denied he was ever physically abusive, which was found to be untrue and cost him his credibility with the Court.

In dismissing the claim, the Court said at [35]-[37]:

“In this case I am satisfied throughout the time the plaintiff resided with the deceased he was physically violent toward her and frequently abused her. I am not satisfied he made any real attempt to reconnect with the deceased after he moved out of home in 1987. There is no evidence after he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder he attempted to contact his mother and explain his earlier actions. He made no contribution to the assets of the estate. While I accept he is in need that need appears to have been occasioned by his own actions. It certainly was not something which was contributed to by the deceased.

As Palmer J notes the question of whether the actions of the plaintiff was such as to disentitle him from making a claim must be judged according to current attitudes and expectations in the community. Section 6(3) does not actually specify a time when the decision is to be made. In my view it has to take into account the history of the relationship between the claimant and the deceased. It is the broad scope of that relationship which I have looked at in reaching my conclusion.

Violence against women is never acceptable. It is at odds with the basic tenant of civilised society. The criminal law in recent times has recognised the unacceptable nature of such conduct and imposed harsh penalties. A person who is violent towards a testator cannot simply expect to be provided for in a will or if not provided for to come before the court and receive a proportion of the estate. The acts of violence reap their own reward. That is exactly what has happened in this case.”

Allegations of historical sexual and/or physical abuse perpetrated by the deceased against the applicant are commonly cited as the reason for an estrangement.21

Invariably, the purpose is to shift the blame for the estrangement onto the deceased. In cases where the evidence is accepted, which is not that common and usually requires objective evidence (i.e. police reports and charges), the applicant is likely to receive provision similar to what they would have obtained if there was no estrangement. However, the Court is rarely in a position to make a finding and often concludes that it was unproven and/or irrelevant.22 In consideration, care should be taken when deciding whether to include allegations of this type and where possible they should be accompanied by corroborating evidence.

There are cases where estrangement alone was considered sufficient to dismiss application for further provision.23 However, to result in a dismissal, an estrangement will usually need to be compounded by other factors, such as violence and/or hostility, or alternatively limited by the needs of competing beneficiaries and/or the size of the estate.

In Leech v Leech-Larkin24, a claim by an adult son who had been estranged from the deceased for 40 years was dismissed. It should be noted that the applicant may have been successful but for the competing beneficiary who maintained a close relationship with the deceased and contributed to the build up of her estate.

In Rogers v Rogers25, the plaintiff was the deceased’s adult daughter, who had been estranged from the deceased for approximately 25 years. The estate was valued at $1,425,945, subject to legal costs. The deceased left her estate to her five other children, with a life interest in real property to one of her sons.

The plaintiff sought further provision of $100,000 to $200,000, on the proviso that payment be made after the end of the life interest.

Hallen J said, when referring to the equivalent New South Wales legislation:

“…the test established by s 59 of the Act has regard not only to what is “adequate” by reference to the applicant’s needs, but also to what is “proper” in all the circumstances of the case. Whether the deceased ought to have made provision for Sandra is influenced by an assessment of her circumstances, including the nature and extent of her present and reasonably anticipated future needs, the size and nature of the deceased’s estate, the relationship between her and the deceased, including her conduct towards the deceased, the competing claims of the other children of the deceased, as other persons with a legitimate claim upon the bounty of the deceased and as the chosen objects of the deceased’s bounty, and the circumstances and needs of each.

The plaintiff’s claim was dismissed with orders as to costs.

Behrens v Behrens26 saw an application by adult son, who had been completely estranged from his mother for over 25 years in a small estate of only $200,000. The estrangement was coupled with the fact that on the last occasion the son saw his mother, he assaulted her.

The deceased left her entire estate to two of her children, to the exclusion of the plaintiff.

The parties were self-represented due to the size of the estate.

In coming to his decision, Rein J said:

In my view, [the deceased] was entitled, notwithstanding that Reginald was her son, to regard him as a person underserving of any benefit from her estate, whatever his financial circumstances at the time of his application and his contribution to the Belfield property more than 25 years earlier. I do not think that [the deceased] was under a moral duty to provide for Reginald or that members of the community would regard [the deceased’s] decision to exclude Reginald as not right or as inappropriate.

Having regard to the circumstances …, particularly the long period of estrangement and the reasons for it, the size of the estate and the situation of the named beneficiaries, I am not persuaded that any order should be made in favour of Reginald. I conclude therefore that his Summons should be dismissed.

An adverse costs order was made against the plaintiff.

In the case of Nielsen v Kongspark27, an adult son sought further provision from his mother’s estate. The estate was small (approximately $335,000) and he had not seen his mother for 18 years prior to her death. The applicant’s conduct included applying to the Guardianship Tribunal for a financial management order when his mother was of sound mind.

In setting out the legal principles with respect to estrangement, Hallen J said at [231] to [237]:

- The word “estrangement” does not, in fact, describe the conduct of either party. It is merely the condition that results from the attitudes, or conduct, of one, or both, of the parties to the relationship. Whether the claim of the applicant on the deceased is totally extinguished, or merely reduced, and the extent of any reduction, depends on all the circumstances of the case: Gwenythe Muriel Lathwell, as Executrix of the Estate of Gilbert Thorley Lathwell (Deceased) v Lathwell [2008] WASCA 256, at [33].

- The nature of the estrangement and the underlying reason for it is relevant to an application under the Act: Palmer v Dolman; Dolman v Palmer [2005] NSWCA 361 , at [88]–[94]; Foley v Ellis at [102]. In Palmer v Dolman, Ipp JA, after a review of the cases, observed, at [110], that:

“… the mere fact of estrangement between parent and child should not ordinarily result, on its own, in the child not being able to satisfy the jurisdictional requirement under the Act.”

- There is no rule that, irrespective of a Plaintiff’s need, the size of the estate, and the existence or absence of other claims on the estate, the Plaintiff is not entitled to “ample” provision if he, or she, has been estranged from the deceased. The very general directions in the Act require close attention to the facts of individual cases.

- The court should accept that the deceased, in certain circumstances, is entitled to make no provision for a child, particularly in the case of one “who treats their parents callously, by withholding, without proper justification, their support and love from them in their declining years. Even more so where that callousness is compounded by hostility”: Ford v Simes [2009] NSWCA 351, at [71], per Bergin CJ in Eq, with whom Tobias JA and Handley AJA agreed.

- As was recognized by the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Hunter v Hunter (1987) 8 NSWLR 573, at 574–575, per Kirby P (with whom Hope and Priestley JJA agreed):

If cases of this kind were determined by the yardstick of prudent and intelligent conduct on the part of family members, the appeal would have to be dismissed. If they were determined by the criterion of the admiration, affection and love of the testator for members of his family, it would also have to be dismissed. Such are not the criteria of the Act. The statute represents a limited disturbance of the right of testamentary disposition. It establishes a privilege for a small class of the immediate family of a testator (the spouse or children) to seek the exercise of a discretionary judgment by the Court for provision to be made out of the estate different from that provided by the testator’s will.

- Even if the applicant bears no responsibility for the estrangement, its occurrence is nevertheless relevant to the exercise of the court’s discretion under s 59(2) of the Act to make a family provision order where the jurisdictional requirements of s 59(1) are met. That the applicant had no relationship with the deceased for some years, and that there did not, therefore, exist between them the love, companionship and support present in “normal” parent/child relationships, during those years, is a relevant consideration: Keep v Bourke [2012] NSWCA 64, per Macfarlan JA, at [3].

- The poor state of the relationship between the applicant and the deceased, illustrated by the absence of contact for many years, if it does not terminate the obligation of the deceased to provide for the applicant, may operate to restrain amplitude in the provision to be made: Keep v Bourke, per Barrett JA, at [50].

The plaintiff’s claim was dismissed.

The learned authors De Groot and Nickel observe that there are other cases involving significant estrangement which could easily have been dismissed for that reason but were ultimately dismissed on other grounds.28

General principles

-

In considering the effect of an estrangement on the appropriate level of provision, an estrangement and the conduct of the parties that led to it is relevant, but it is to be considered in the context of all of the relevant factors (i.e., the needs of the applicant; the size of the estate; the needs of the competing beneficiaries and their relationship with the deceased; etc). In other words, an estrangement is not like to be the “smoking gun”.

-

Estrangement, even a long estrangement, is unlikely to be sufficient to override the testator’s moral obligation to provide for an eligible person.

-

A long estrangement in a small estate may result in the application being dismissed with orders as to costs.

-

An estrangement, particularly a long one, may restrain the amplitude of an order for further provision.

- The Court considers who is to blame for the estrangement:

- If there is fault by both the testator and applicant, but more of the blame lies with the testator, the award is likely to be greater than if the blame was solely attributable to the applicant.

- If the deceased was the primary cause, the estrangement may be completely or substantially disregarded when assessing what is adequate and proper.

- If the applicant is to blame, further provision is likely to be substantially reduced or even withheld.

- The court will take a robust view of the conduct of the parties and despite the views of the testator and the litigants, may find the reasons to be not so serious or even trivial.

- The needier the applicant, the more significant the estrangement and associated conduct will need to be to disentitle them from provision or result in a substantial reduction in the provision.

- If the estrangement is accompanied by hostility directed towards the deceased, the provision is likely to be substantially lower.

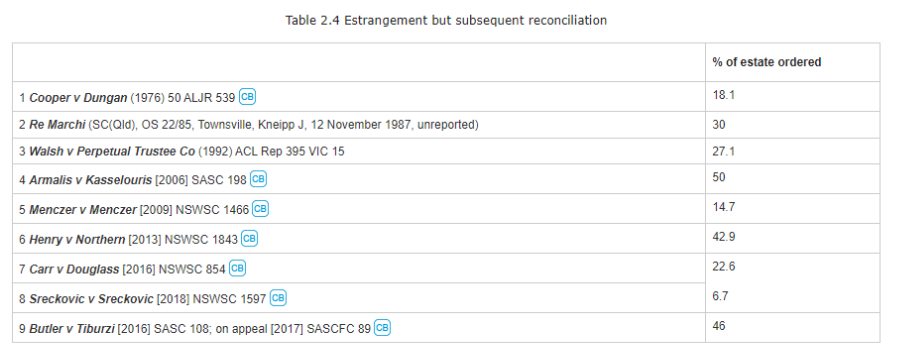

- Efforts made by the applicant to reconcile with the deceased are relevant and may increase the provision awarded. If reconciliation is successful after a period of estrangement, the provision may reflect what would have been ordered if the estrangement did not occur.

- If the estrangement occurred following some disentitling conduct by the applicant, provision is likely to be substantially lower or withheld. Some examples of conduct held to be disentitling include:

-

Acts of violence against the testator;

-

Chronic drunkenness;

-

Domestic violence;

-

Committing a serious criminal offence resulting in a prison sentence, which brought shame to the testator’s family;

-

Attempting to have a sane testator committed to a mental institution; and

-

Acting dishonestly (theft/fraud against the testator; failing to account for profits from a family business; etc).

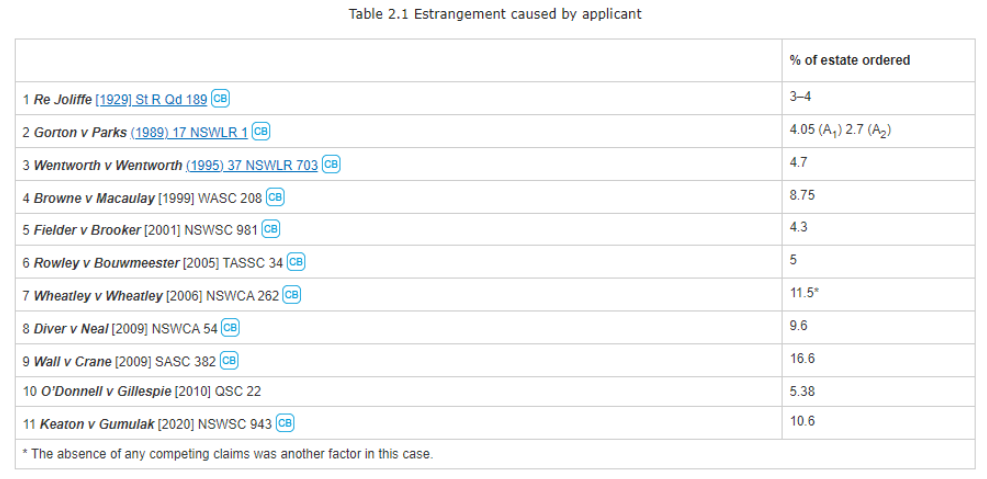

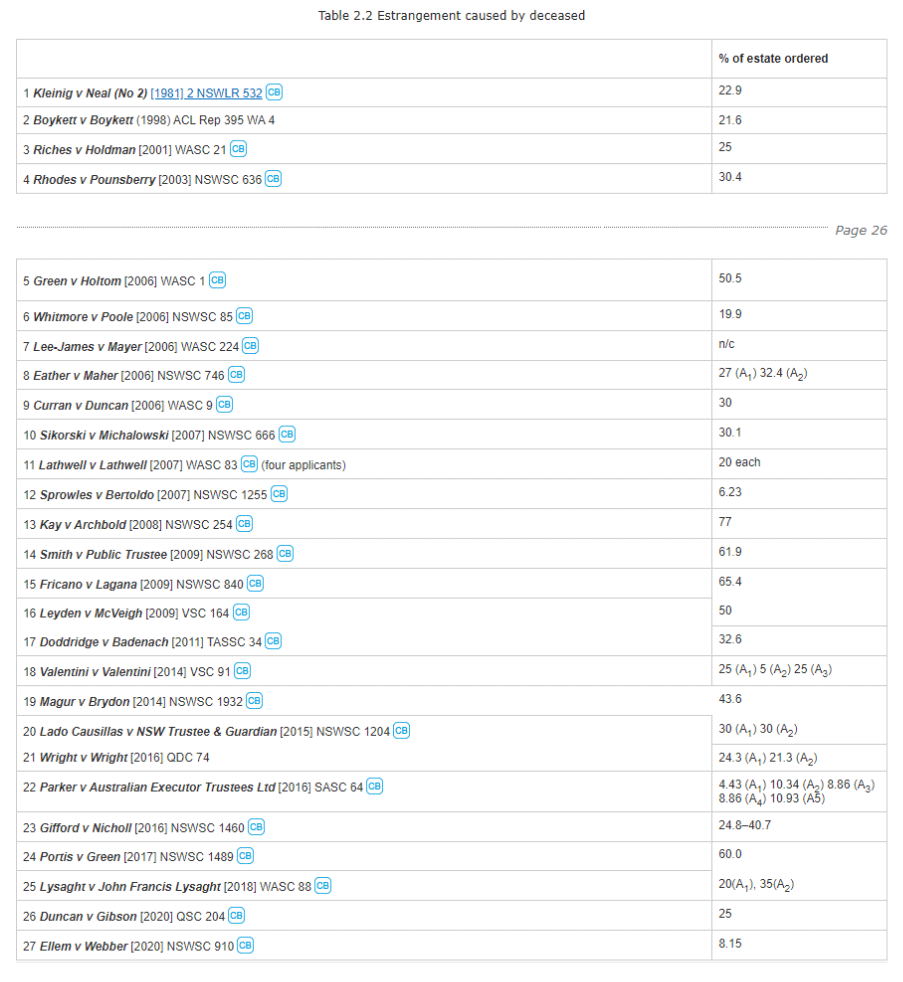

The learned authors De Groot and Nickel provide useful illustrations of the application of some of these principles in their text, Family Provision in Australia.

PRACTICAL STEPS

Taking will instructions

-

It is critical that the testator’s instructions are recorded in detailed file notes, ideally accompanied by a properly completed Lexon will instructions sheet.

-

The testator should be asked about all of their family members, not just those they wish to benefit from their estate. A family tree diagram is useful.

-

If the testator’s instructions reveal that their estate will be at risk of an application for further provision (e.g. where they are not providing an equal distribution between their children), they should be advised of the risk, including the potential legal costs of such an application and the lasting impact it will leave on their family.

-

The testator should be encouraged to make a detailed sworn statement, in the form of a statutory declaration or affidavit, which can be used as evidence in any future claim against the estate.

-

At a minimum, the statement should address:29

- The nature and duration of the initial relationship, e.g. parent/child, de facto partner, domestic partner, former de facto partner, member of household.

- The testator’s understanding of the reasons for the breakdown of the relationship, if applicable.

- Details of any provision made by the testator for the potential applicant during their life time, and any matter which the testator believes should disqualify the potential claimant from seeking further provision.

- Any serious criminality on the part of the potential claimant (lengthy gaol sentences for serious offences) and the testator’s reaction to that criminality (shame within their community, embarrassment).

- Any other relevant or “disentitling” conduct of the potential claimant, such as those described above.

- A word of warning, poorly prepared and/or inaccurate statements may assist the applicant. For example, in Pincius v Wood [1998] TASSC 46, Cox CJ noted, at 4:

“A reason based on a belief proved to be mistaken may well be relevant in support of an applicant's claim. Thus, if the reason advanced for inclusion is a mistaken belief in the prosperity of an applicant who enjoyed a good relationship with the testator that could properly be taken into account and would be a strong reason for interfering with the will…” -

The testator should also be advised that there are steps available to mitigate the impact of any family provision application, which include but are not limited to:

- Transferring ownership to joint tenancies (noting the impact of the notional estate provisions in New South Wales);

- Making gifts to intended beneficiaries while they are alive;

- Transferring assets to inter vivos family trusts;

- Use of binding death benefit nominations to keep superannuation and life insurance proceeds out of the estate.

- Finally, the testator should be advised that it is not possible to provide any meaningful advice as to the prospects of any potential family provision application, without taking detailed instructions regarding the circumstances of the likely applicant and each of the competing beneficiaries. Naturally, this will incur additional expense and delay.

Advising executors and applicants for further provision

Executors and applicants alike will come to the matter with preconceived notions relating to the impact an estrangement will have on an entitlement to further provision. It is critical that they are appropriately advised from the outset, so their expectations are properly managed and the communications with opposing parties operate within the bounds of reality. Otherwise, the client is likely to be disappointed with the outcome and any goodwill which may have been cultivated between the parties will be destroyed, leading to increased cost and delay.

The client needs to be advised of the following:

-

An estrangement, even a very long one, does not automatically disentitle an eligible person from further provision.

-

The court will give careful consideration to the reasons for the estrangement, including whether the applicant or testator were more responsible for the estrangement, noting the potential outcomes detailed earlier in this paper. Therefore, a detailed history of the relationship between the applicant and the testator is necessary, akin to the information to be obtained from the testator in the will instructions phase. It is the writer’s experience that executors and applicants can be prone to downplaying or omitting facts which they perceive as damaging to their prospects, while exaggerating circumstances which they perceive as helpful; both of which impact on the lawyer’s ability to provide accurate advice. Sometimes it can be enlightening to ask the client what they think the other party is likely to say about the estrangement and any related conduct.

-

The estrangement and the conduct that led to it and maintained it, is only one of the relevant factors to be considered in assessing whether the provision made by the deceased was proper and adequate. As such, the impact of an estrangement may be substantially overcome or completely overcome if the other factors warrant it (i.e. needy applicant; large estate; etc).

-

If the matter involves allegations of historical abuse, the client should be advised that while they are relevant in the consideration of who is to blame for an estrangement, the Courts are generally unwilling to make findings without corroborating evidence. Additionally, they should be advised that the purpose of family provision applications is not to provide compensation for past abuse.

-

If the estate is small (e.g < $500,000), an estranged applicant may be at a high risk of an adverse costs order if unsuccessful.

-

If the estate is large, the court is more likely to award further provision. However, a large estate does not always equate to substantial provision for estranged applicants.30

-

If the estrangement was coupled with hostility or other disentitling conduct by the applicant, the amplitude of the provision is likely to be significantly reduced or withheld.

-

The courts have a wide discretion to make orders for further provision, the exercise of which turns on the facts of each case. There are no scales of injury or assessment of lost future earnings as there are in personal injury cases, nor is there a specific loss being claimed as there is in most other civil litigation. As a result, there are many cases where one judge will order further provision in circumstances where others would not, and vice versa. Consequently, the likely award of further provision is inherently difficult to predict, and it is only the most obvious of matters where success or failure can be accurately predicted. Even then, what is obvious to one practitioner may not be so obvious to another.

By Sean Powell

Sean leads the Wills and Estates Litigation Team at Robbins Watson Solicitors, a law firm specialising in contested wills and estates He has a Masters Degree in Applied Law, with a specialisation in Wills and Estates.

You can book a free case appraisal with Sean or one of our other Gold Coast Estate Litigation Lawyers here. You can also select Begin Online to get started with your estate dispute online.

1 Brayne C. The elephant in the room- healthy brains in later life, epidemiology and public health. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:233–239; Xie J, Brayne C, Jagger C, Bond J, Matthews FE. The oldest old in England and Wales: a descriptive analysis based on the MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing study. Age Ageing. 2008;37:396–402.

2 RBC Wealth Management Services. Wealth transfer and the next generation. Perspectives. 2017;5(1). [accessed August 2023]. https://www.rbcwealthmanagemen....

3 (1994) 181 CLR 201, 209-210.

4 [1938] AC 463, 478-9.

5 Ibid, 479.

6 Freeman & Ors v Jacques [2006] 1 Qd R 318 per Keane JA at [29], citing Vigolo v Bostin [2005] HCA 11 at [6], [16] – [18], [22], [25], [27], [74] – [75] and [114]; (2005) 221 CLR 191 at 197, 200 – 201, 202 – 204, 204 – 205, 218 – 219, 225.

7 [2008] WASCA 256.

8 (1980) 144 CLR 431; [1980] HCA 14, at 440.

9 [1948] VLR 279, at 280.

10 (1979) 143 CLR 134.

11 [2013] NSWSC 357, [128].

12 [2005] NSWCA 361 at [110].

13 [2006] NSWCA 262.

14 [2008] NSWCA 288.

15 Ibid, at [101].

16 Ibid, p 22.

17 [2011] TASSC 34.

18 [2016] QDC 74.

19 [2006] NSWCA 262, at [37].

20 [2016] WASC 45.

21 See for example: Barrass v Kaine [1999] NSWSC 245; Rhodes v Pounsbury [2003] NSWSC 636; Rowley v Bouwmeester [2005] TASSC 34; Bentley v Brennan [2006] VSC 113; Lawrence v Campbell [2007] NSWSC 126; Cameron v Cameron [2009] SASC 27; Kennard v Sheehan [2010] NSWSC 882; Evans v Levy [2010] NSWSC 504; Williamson v Williamson [2011] NSWSC 228; Jones v Smith [2016] VSCA 178.

22 Lawrence v Campbell [2007] NSWSC 126; Williamson v Williamson [2011] NSWSC 228; Cameron v Cameron [2009] SASC 27; Evans v Levy [2010] NSWSC 504.

23 See for example: Scales’ case (1962) 107 CLR 9; Shearer v Public Trustee [1998] NSWSC 1007; Hogan v Clarke [2002] NSWSC 386; Monaco v Keegan [2006] NSWSC 825; Ford v Simes [2008] NSWSC 1120, affirmed on appeal [2009] NSWCA 351; Hansen v Hennessey [2014] VSC 20; Morris v Smoel [2014] VSC 32; Underwood v Gaudron [2014] NSWSC 1055; Rogers v Rogers [2018] NSWSC 1982; Re Estate Luce [2020] NSWSC 117.

24 [2017] NSWSC 1418.

25 [2018] NSWSC 1982.

26 [2020] NSWSC 1566.

27 [2019] NSWSC 1821.

28 De Groot & Nickel, Family Provision in Australia, 2006 (6th ed), p 23; Booth v Booth [2002] NSWSC 836; Menaker v Kutylov [2006] NSWSC 374; McDougall v Rogers [2006] NSWSC 484; Cassaniti v Cassaniti [2008] NSWSC 258; Tiedeman v Tilse [2009] NSWSC 234; Barbanera v Barbanera [2017] NSWSC 357; MacAlpine v MacAlpine [2020] NSWSC 824.

29 Margaret Pringle, Cut off and Cut Out: Estrangement in Family Provision Applications, TVED, 10 November 2021, p 4.

30 See for example: Limberger v Limberger; Oakman v Limberger [2021] NSWSC 474 where the applicant received provision of $600,000 in an estate worth over $9 million.